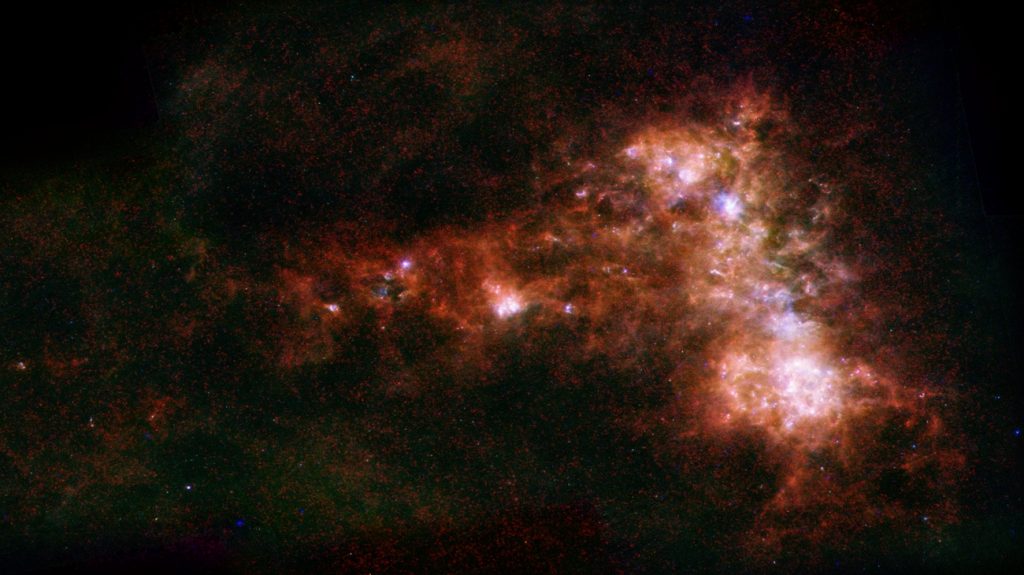

Astronomers have discovered that dozens of dwarf galaxies are experiencing a baby boom at the same time.

You expect that galaxies more than a million light years apart will not coordinate their birth plans. But it appears that the dwarf galaxies carried out by scientists are led by astronomer Charlotte Olsen (Rutgers University, USA). Rusk with mice hasn’t been around for a while.

Read also:

Birth wave

Olsen and her team It examined 36 dwarf galaxiesWith the help of the Hubble Space Telescope, among other things. These observations showed that about 6 billion years ago there was some calm in the nurseries of these systems. Fewer and fewer new stars were born. But this picture changed 3 billion years ago. More and more stars would have been seeing the light since then.

Star formation can increase when galaxies collide or interact with each other, and decrease when stars run out of gas (usually hydrogen). In this case, astronomers believe that a large-scale change three billion years ago caused the birth boom in nearly all of the 36 galaxies studied.

The exact type of this change is not yet known. One of the proposed possibilities is a decrease in the energy-rich radiation in the environment. The gas clouds are said to have cooled, making them more likely to clump together into new stars.

Difficult to study

“An interesting discovery,” says astronomer Marcel Van Dalen of Leiden University. He cites the increased amount of gas from outside as another possible explanation for the baby boom. “And so suddenly more gas is available in galaxies to form stars.”

Astronomer Eileen Tolstoy at the University of Groningen thinks astronomers’ conclusions are still very speculative, she says. De Volkskrant. Dwarf galaxies are difficult to study if they are hundreds of thousands of light-years away from us, so she says there are still many uncertainties in the measurements of Olsen and her team.

Astronomer Filippo Fratternale, who is also from the University of Groningen and was not involved in the research, agrees with Tolstoy: “More studies are definitely needed in the future to confirm this finding. There are two new telescopes very important for these studies, the ESO Extremely Large Telescope in Chile and the James Webb Telescope. Hopefully, JWST will launch later this year (in October).

Resources: The Astrophysical JournalAnd the Informed dailyAnd the De Volkskrant

“Coffee buff. Twitter fanatic. Tv practitioner. Social media advocate. Pop culture ninja.”

More Stories

Which can cause an increase in nitrogen.

The Central State Real Estate Agency has no additional space to accommodate Ukrainians.

The oystercatcher, the “unlucky national bird,” is increasingly breeding on rooftops.